- Home

- Craig Bellamy

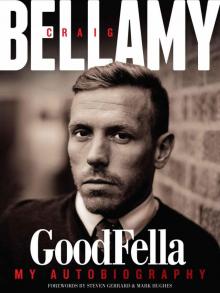

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella Read online

By Craig Bellamy with Oliver Holt

Copyright: Craig Bellamy

Published by Trinity Mirror Sport Media

Executive Editor: Ken Rogers

Senior Editor: Steve Hanrahan

Editor: Paul Dove

Senior Art Editor: Rick Cooke

Production: Chris McLoughlin, Roy Gilfoyle, James Cleary

Design: Colin Harrison

First Edition

Published in Great Britain in 2013.

Published and produced by: Trinity Mirror Sport Media,

PO Box 48, Old Hall Street, Liverpool L69 3EB.

ISBN: 9781908319388

Photographic acknowledgements:

Craig Bellamy personal collection,

Trinity Mirror (Daily Mirror, Western Mail, Liverpool Echo),

PA Photos, Football Association of Wales,

David Rawcliffe.

Front and back page images: Tony Woolliscroft.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the copyright holders, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

I

Acknowledgements

First of all, I want to thank my kids, Ellis, Cameron and Lexi, the three most important people in my life. I hope I’ve made you all proud.

My mum and dad have always loved and supported me and I’m so grateful for the fact that we are as close again now as we ever were.

My brothers Paul and Matthew are two good men who I’m proud to call my family.

Sometimes divorce obliterates the good memories but my ex-wife Claire and I shared some happy times in our years together before we grew apart and went our separate ways.

I’d like to thank every manager that has had to put up with me. They have all left a mark on me. I didn’t really want to mention any of them individually but after this season with Cardiff, I have to state my gratitude to Malky Mackay. He’s been tremendous.

I could not have asked for a better agent than Steve Horner. His advice has been fantastic. I might not have listened to him all the time but I should have. I wouldn’t have got into as much trouble.

Phil Baker, my business adviser, has been a good source of advice, too, as well as a mate. And my PA, Suzanne Twamley, has been a true friend who has been watching me play football since I was eight.

Dr Steve Peters has had a huge impact on me and still does now. He has shown me what happiness is.

I am not the easiest person to work with when I’m recovering from injury so I’d like to thank all the physios down the years who have allowed me to keep playing. I would like to single out Andy Williams, the knee surgeon, as well. A huge thank you to him.

Not many people know Kieron Dyer properly but I am grateful for the fact that I do. He’s an intelligent man and my best friend in football.

I owe a lot to Dato Chan Tien Ghee, better known as TG, the former Cardiff City chairman. His determination to get me to come to Cardiff never waned and his passion was amazing. He had many kind words for me in tough times.

In the moments after we won promotion, I was lucky to be able to share some of the joy with the Cardiff City doctor, Professor Len Nokes. I can’t think of anyone I would rather have been with right then.

I want to mention James Reardon, better known as Jimmy Ray, a great friend of mine who died too soon.

I want to mention all the clubs I have played for, all the people who work for those clubs, all the fans who support those clubs.

And, of course, I want to mention Gary Speed. The impact he had on my career while he was here was incredibly important. In a strange way, his influence on me since his death has probably been even greater.

Craig Bellamy, 2013

For Nana Mary.

Not a day goes by when

I don’t think of you.

II

Foreword

by Steven Gerrard

When I first heard that Craig Bellamy was joining Liverpool in the summer of 2006, I thought that, as captain of the club, I might have a challenge on my hands.

I had played against him, had a few spats and arguments and words. I was expecting a bit of a hothead. I was expecting someone who was more interested in being a footballer rather than actually living like one.

I was totally wrong. It was my fault. I was guilty of judging someone before I had met him. And when he arrived, he was the opposite of what I thought he would be.

Nothing surprised me on the pitch because I had seen him with my own eyes. I knew he was a good player and I knew he would offer us a lot.

But his character surprised me. It surprised me how professional he was. It surprised me how much he loved the game.

He is a bit similar to me in a way. He has got certain small insecurities. If he doesn’t train well or play well, it hurts him. And if he loses, it hurts him. But I think they’re great insecurities to have as a player because they help you to find consistency and they help drive you to the top. But you wouldn’t think that of Craig if you hadn’t met him. You’d think he’d be a person who doesn’t care. Well, he isn’t.

On the pitch, he is one of those players that you would rather have with you than against you. Everyone knows what he can do. On his day, he can destroy any defender out there because of his pace. When you are playing against a side he is in, every manager is wary of Craig Bellamy. It’s his character, too, the way he never gives up, the way he never stops harrying you and hassling you.

He played for Liverpool in two different spells, of course. The first time he came, when Rafa Benitez was the manager, I was disappointed he did not stay longer than a single season. I thought that, if he had stayed, he would have offered us more and more. I felt we would have been a better team with him in it and when he left, we didn’t really find anyone of his quality to replace him.

I wanted him to stay. He was a player with real quality and that is one of the reasons the club brought him back. After his second spell at Anfield in 2011-12, I understood why he wanted to go and play for Cardiff City and to be closer to his children. I know that he is a Liverpool fan but he loves his hometown club, too. I think he has got the same love for Cardiff that I have for this club.

I think what people will admire about this book is that there will be an honesty about it because there is an honesty about him. A lot of footballers say the politically correct thing. They want to be liked too much. Sometimes, you have to say what you really think and be honest and I respect Craig’s honesty.

When you are a footballer, people say you have to respect the media but he hasn’t done that really. Rather than saying the nice thing over and over again, he has said what he thinks and sometimes that upsets people.

At Liverpool, he worked incredibly hard in the gym and set a good example of how a senior pro should behave. If he saw anything around the place that suggested people weren’t pushing in the right direction, he would help you as a captain and back you up. He wanted the right thing for this club.

He ended up being a terrific ally for me at Liverpool, as well as becoming a good friend.

Steven Gerrard, 2013

III

Foreword

by Mark Hughes

If I had to pick out one reason why I always loved having Craig Bellamy in my football teams, it is the intensity he brings. It’s his desire to affect the game every single time he plays. He has a strong will and I like that about him.

Some people thought he was trouble without

ever really getting to know him. Some of the things he does can be misinterpreted and maybe there were some who did not like his intensity. Maybe some of them were unsettled by it or worried about the reputation he earned in his younger days.

Sure, there were numerous occasions when he played for me for Wales, Blackburn Rovers and Manchester City when he looked like he was going to combust on the pitch. I didn’t have any dramatic remedy for that. There was no particular secret. I just gave him a smile and a knowing look and he tended to calm down fairly quickly.

He was always a great asset to me. He is the type of player the fans love because they know he is giving it everything he has. He inspires players around him, too.

It has never really occurred to me that he is difficult to manage. I actually always found him very rewarding to manage. If you understand him and support him, he will play his heart out for you.

I played with him for Wales when he was younger and, yes, he could be quite volatile but a lot of people have also been surprised by how professional he is.

Like most of us, he has changed as he has grown older. He had some injuries and the fear of losing a career that was precious to him turned him into someone who is utterly dedicated to the game.

He doesn’t take any prisoners. He says it as he sees it. He is honest and up front and he expects people to be the same with him.

He has got a lot of strengths. Diplomacy isn’t one of them.

Mark Hughes, 2013

Introduction

The Human Snarl

I don’t know what you see when you look at me. A human snarl, maybe. That’s pretty much been my image for the last 15 years. A snarling, snapping, hungry, feral player who loathed himself and everyone around him. Someone who was unhappy. Someone who had a lot of things eating at him. Someone always moving on. Always falling out with people. Always running.

I have always been restless. That’s true. Restless in my personal life and in football. In my own world, maybe I feel I deserve more respect than I get as a player so I am always chasing it as aggressively as I can. And if I don’t get it in one place, from a manager or from a crowd, I search for it in another place.

Steven Gerrard says I am driven by my insecurities. He’s right. I’m always looking for a chance to show people how good I am. I went through much of my career without winning anything. So I started to chase trophies. I went to clubs where I thought I would win medals. When I failed, I moved on. I wanted something to show for my career. If I didn’t win medals and trophies, my career was just a big waste. I was convinced of that. The fear of failure was one of the reasons I kept on moving.

That changed in November 2011 when my friend Gary Speed died. I was playing for Liverpool then and the club doctor, Zaf Iqbal, said he was worried about my mental state. He said he thought I needed help. He recommended that I went to see Steve Peters, the psychiatrist who is probably most famous for working with Britain’s gold medal cyclists Sir Chris Hoy and Victoria Pendleton.

I had always refused to see a psychiatrist before. You may not be surprised to know it had been suggested to me several times. And there were excellent practitioners available at several of the clubs I played for. But I thought it was weak to seek that kind of help. I thought I was doing okay. I was a good footballer. I didn’t want to talk to anyone in case it opened up a mess of issues that would affect my game. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. That was what I thought. But it clearly was broken. I was broken. I was just in denial about it.

As a young kid, I was happy. I grew up on an estate on the outskirts of Cardiff. I had loving parents and a group of close mates, many of whom spiralled off into delinquency and drugs. I loved football and played every minute I could. I was a daydreamer, yeah, and I didn’t achieve much at school. But I was happy. And then I had to move away when I was 15.

I moved to the other side of Britain, to Norwich, to play football, to pursue my dream. It sounds melodramatic but it killed a part of me. It taught me to isolate myself, to be single-minded, to be selfish, to exclude others, to keep everything inside. I learned to be emotionally detached. I grew distant from my mum and a lot of people who were close to me.

The more I rung home back then, the more I missed home. Nothing makes it better. In fact, everything seems to make it worse. You ring home, you get upset, your parents get upset because they can tell how unhappy you are and they can’t do anything about it. And then you start feeling guilty because you’re upsetting them. And before you know it, you’re in a phone booth outside a fish and chip shop in Norwich crying your eyes out.

That’s what it was like for me. That’s what it was like for a year. A year of homesickness that hurt like hell. A year of trying to conceal my feelings. A year of trying to cope with everything that was being thrown at me as a young footballer trying to make it with hard taskmasters for coaches and senior professionals that enjoyed treating you like shit. Sounds like self-pity, doesn’t it? Well, I was the master of self-pity.

I spent most weekends on my own. I played a match on Saturday morning, watched the Norwich first team play in the afternoon. Then I’d stick around, clean up all the kit, watch the players and study their happiness in victory or the raw pain of defeat. Then it was the long walk home to my digs at The Limes, half an hour in the dark. Sit in my room for a while on my own. Then go to the chip shop. And the phone box.

I had a girlfriend by then. Claire and I got together before I left Cardiff. In time, we had three beautiful children together. We got married in the end. And we stayed married until 2012 when she decided she’d had enough. Enough of the moving and the following me round. Enough of the absentee husband. Enough of the selfishness and the black moods and the times when I wouldn’t talk to her because I was worried about a knee injury.

So we got divorced and it nearly tore me apart. I have had months of guilt about not being the husband I should have been. And not being the father I should have been, either. For a while, I didn’t think about the lifestyle I had been able to give Claire and my three children, the life I have been able to give my kids who mean more to me than anything in the world. The pride in what I have been able to provide, the pride in some of the sacrifices I made, has come back now.

I caused the breakdown of my marriage. Not football. It’s about more than football. I suppose this is controversial because people will say that no two people are the same but I feel that high-profile sportsmen and sportswomen are different. We’re wired differently. We’re not the same as other people. The same goes for a lot of other people who are very successful at what they do.

Why? Because we have to sacrifice so much. And some people can cope with that and maintain a happy family life. And some people can’t. I had no experience of being around people who were doing something similar. There were no people in my area who were following that path. I had to learn for myself. I never asked for advice and saw how they behaved.

The way I saw it, my life would begin when I was 35. When I finish football, my life starts. That’s how I looked at it. Until then, nothing matters. It’s the game and that’s it. I want to be as successful as I can. I want to earn as much money as I can for my children. And then I can sit back and relax.

The thing is, you have to enjoy what you are doing at the time as well. Otherwise you’re just punishing yourself. The sacrifice is too great. I didn’t understand that. Not until it was too late. Too late for my marriage anyway. I missed out on years and years of fun. I didn’t enjoy it. Not even close. I didn’t enjoy my career. If a team-mate made a mistake, I might not speak to him for a week. It was bullshit.

If I did something good in a game, I’d just tell you about all the bad things I did instead. That’s what kept me up at night. And I thought keeping myself up at night was improving me. If I woke up at 3am, thinking about something I didn’t do, that’s what made me a better player. If I wasn’t doing that, I thought I was taking my eye off the game. If there was a game on television on Friday night and I didn’t watch it

, I thought I was showing football a lack of respect and I would pay for it on Saturday. That’s how crazy I was.

I wouldn’t leave the house two or three days before a game because I wanted to save my legs. If I didn’t save my legs, I thought I would pay for it on Saturday. If I won on a Saturday, I would wake up at the same time the next Saturday, leave the house at the same time, drive the same route to the game, wear the same suit. If I was forced to do something differently, I was convinced I was going to lose. It was borderline insane.

So, yes, I was difficult to live with. I worked away a lot. I was apart from my wife and family for long periods. Several years ago, they moved back to Cardiff to give my children a stable base for school and I commuted from London or Liverpool or Manchester or wherever I was playing to see them. It’s hard to have a successful relationship when you’re living like that.

Being away from my kids on a daily basis made me very unhappy so why the hell was I doing it? Why did I put myself in that situation? I felt that when I came home, it wasn’t my home. I felt guilty for not being around the children so I tried to make up as much time as I could with them in the short while I had. But I also had a young wife who wanted my time and affection and I couldn’t do it all at once and the next thing I am back up the road.

That was part of the reason I became the human snarl. I was unhappy and if I was going to be unhappy, I wanted to make damn sure everyone knew I was unhappy and that they were unhappy, too.

It took the death of Gary Speed for me to step back and find happiness within myself. It wasn’t my wife’s fault that I had been unhappy. It wasn’t a club’s fault or a manager’s fault. It wasn’t because I had had an argument with Graeme Souness or Roberto Mancini. I was stopping myself from being happy. I’d been doing it since I left Cardiff at the age of 15.

If I had not got help, if I had not begun talking to Steve Peters, I was facing a dark, empty future. Gary Speed’s death, the fact that he apparently took his own life, shook me to the core. It scared me. There are a lot of similarities between me and Speedo.

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella