- Home

- Craig Bellamy

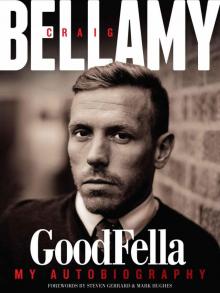

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella Page 15

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella Read online

Page 15

I held on for another month until the game against Serbia and Montenegro in Cardiff in mid-October. I played for Newcastle against Everton at Goodison and we finally got our first point of the season. Despite the result we were bottom of the table and Sir Bobby Robson was forced to deny rumours that he had resigned. We drew at home to Bolton and lost at Arsenal and then, a week before the Serbia tie, we finally got our first win of the season with a 1-0 win over Southampton.

Then it was Serbia. It felt like I had to make one last push to play in that game and hope beyond hope that we won and Italy slipped up at home to Azerbaijan. It didn’t work out like that. There was no pressure on the Serbs because they knew they could not qualify and so they played with freedom. We lost a silly early goal when a free-kick squirmed past Paul Jones but then Harts equalised with a penalty.

By the second half, though, we knew that the Italians were 2-0 up against the Azeris and we faded away. Savo Milosevic put the Serbs ahead eight minutes from the end and they scored a third before Rob Earnshaw got a consolation for us with a header. But that was it. We had finished second in the group, four points behind Italy, who had beaten Azerbaijan 4-0.

We drew Russia in the play-offs but they were a month away and I knew I couldn’t make it. I couldn’t go on playing any more. Every time I played, it was like torture. In my absence, Wales drew 0-0 with Russia in Moscow and then fell to a 1-0 defeat in the second leg in Cardiff. I didn’t go to the game. I probably should have done but I was so down and depressed that I didn’t want to risk visiting my mood on any of the other lads. I watched it at home in Newcastle. When the final whistle went, it was heart-wrenching.

There was a late chance of a reprieve when it emerged that one of the Russians, Egor Titov, had failed a drugs test before the second leg. It turned out to be false hope. “In reviewing the case,” Uefa said, “the Uefa Control and Disciplinary Body made reference to the FAW’s failure to provide evidence that the player was under the influence of a prohibited substance in the second-leg match. In addition, and according to Uefa regulations in the case of a doping offence, the punishment anyway only applies to the player himself and not to the team.”

So that was it. My best chance of playing in a major tournament was gone. I tried to put it behind me and concentrate on rescuing my career. I flew to Colorado after the defeat to Serbia and had an operation on my left knee and a course of heavy friction on my right knee. They said I’d be out for four months.

In some ways, it was a blow. In others, it was relief. I had been in so much pain, I had been trying to satisfy so many people, that it had worn me down. I was trying to do my duty for my country and respect the people who paid my wages but in the end I wasn’t doing anybody any favours. Not Wales and certainly not Newcastle. All I’d done, actually, was make myself look like an idiot.

15

Change At The Top

Before I had even left America after the knee operations, I got a message saying that Freddy Shepherd wanted to see me as soon as I got back. I knew it was going to be interesting. I went into his office on crutches. He barely looked at me. He barked ‘sit there’ at me. I didn’t know what to do with my crutches. I didn’t want to lay them on his oak table so I left them on the floor.

He didn’t mince his words. He said everyone on the board wanted me out of the club and so did he. They had run out of patience with me, he said.

“I know what you did,” he said. “But did Wales pay for you to go to America for your knee operation? Did Wales pay the surgeon’s fees? No, of course they didn’t. So you better make sure you work your arse off to come back as good as you were before because if you don’t, we will get rid of you as fast as we can. And I don’t care how much we get for you or who buys you.”

For once, I didn’t have a lot to say. I knew I wasn’t in a position to have a go back at him so I just sat there and took it.

“Get out of my office,” he said, and I picked up my crutches and left as fast as I could.

I was in a bit of a daze. I was so down and depressed that I had no fight left in me. I was 24 years old and I’d had four knee operations. Because my ambitions were ridiculously high, I put too much pressure on myself to try to fulfil them and if I didn’t, I saw myself as a failure at everything. It’s a difficult way to go about your life.

I withdrew from everyone. I never went out with the rest of the players any more. I knocked all that on the head because drink was the last thing my tendons needed. I just felt isolated. I wasn’t socialising with anyone any more. I would come in to the training ground and hardly speak. And if I did speak, I didn’t have anything nice to say because I was feeling so bitter.

During my rehab, I made a conscious decision that I would come in later in the day when all the other lads had left training. And that’s what I did. I didn’t see anyone. I just knuckled down. I had my two boys, I had Claire, we had a lovely new house over near Morpeth and I focused on them and stuck my head in rehab.

I just wanted to come back strong and playing properly again. I wanted to play without constant pain. I heard horror stories about what had happened to the careers of players who had troubles with patella tendons. The Brazilian Ronaldo’s was the worst. They blighted his career. Those stories, and the idea that I might never be the player I once was, tormented me.

Christmas was just a blur. God knows how Claire put up with me. I wouldn’t go anywhere because I didn’t want to bump into anyone. I was afraid I was cracking up because of what the injuries had done to me. But after a couple of months, I began to feel a little more optimistic. I started to jog and it felt different. My right knee felt good because of the friction I had done on it. That treatment numbs your nerve endings and stops the pain. Actually, I started to feel great. I was just praying it lasted.

For once, I was waking up in the mornings without being crippled by pain. Until then, I’d been waking up in the middle of the night and my knees had felt like they were on fire. But now they felt normal again. I played one reserve game and it went well. I felt like I could be a good player again.

I played my first match for Newcastle for nearly four months on the last day of January 2004, against Birmingham City at St Andrew’s. I came on for the last 15 minutes and it felt like the beginning of a second chance. I came on for the last 11 minutes of the game against Leicester City at St James’ Park the following weekend and that was emotional, too.

Then I got my first start against Blackburn Rovers at Ewood Park and scored a volley in a 1-1 draw. I was absolutely flying by then. I was just so grateful to be back. Lucas Neill tackled me hard just before half-time and I was worried for a little while and disappeared for some treatment in the changing rooms.

I don’t think people expected me to come back on after half-time but I actually felt encouraged by the fact that my knee had stood up to the challenge and seven minutes into the second half, I put us ahead after a mistake by Brad Friedel. I celebrated that goal like a madman. It was my first in the Premier League for 11 months.

While I had been gone, the team had recovered from our dreadful start and that draw at Blackburn moved us into fifth place in the table, level on points with fourth-placed Liverpool in the race for the final Champions League spot. Arsenal were in their Invincibles season and they, Manchester United and Chelsea were out of sight but we were confident we could finish above Liverpool.

I was thrilled to be back but then there was another setback. Quite soon after my return, I was involved in an argument with the club doctor and he went straight to Freddy. I was summoned to his office again. He said it was obvious I had not listened to a word he had said during our last meeting and that he had enough. But I wasn’t going to sit there and take it this time. This time, I was ready for him.

“You talk all this talk about how you’ll get rid of me,” I told him, “but as long as I am at this football club, the manager will play me. I bet you any money. If I don’t play and I am sat on the bench, the crowd will sing my name. And I will

tell them why I am not coming on, because you are not allowing it. And you answer to them. Otherwise, bring my value down and let me go to a club I want to go to.”

I thought he was going to come back at me all guns blazing. I was expecting a full-on argument. I was relishing it. I was thinking ‘don’t threaten me, fucking act’. But he took me by surprise.

“That’s exactly the response I would have given,” he said, beaming. “That’s the player I want. Now you’re fighting. That’s the player we bought.”

I was stunned. It was obvious Freddy considered the meeting over so I went to shake his hand as I was leaving.

He stopped me. “No,” he said, waving away my hand. “Hug.”

So I gave him a hug and as I was hugging him I was thinking ‘is he for fucking real?’

I scored four goals in my first seven games back and we were neck and neck with Liverpool for fourth place. But the mood at the club had changed while I had been injured. There was a lot more talk about how Sir Bobby had lost the dressing room and the fans seemed discontented with the fact that we were not challenging for the title.

The rumours about Sir Bobby losing the dressing room simply weren’t true but circumstances around us had changed. Roman Abramovich had taken over at Chelsea and was pumping money into the club. Liverpool had staged a recovery and were stiff competition again. Arsenal were better than ever. Manchester United would continue to be out of our reach.

So the top four was the limit of our ambition as far as the Premier League went and after the previous two seasons, the Newcastle fans struggled to adapt to that. Freddy Shepherd was scathing about the players, too. He said we had Rolls Royce facilities but we were playing like Minis. Despite the fact that we were among the top sides, there was a lot of dissatisfaction among the supporters.

We made the semi-finals of the Uefa Cup that season, too, but lost to Marseille 2-0 on aggregate after two goals in the second leg from Didier Drogba. I missed that game. In fact, I’d pulled a hamstring against Aston Villa in the middle of April and missed all but the final league game of the season against Liverpool. They were four points ahead of us by then so we could not catch them for fourth. We drew 1-1, finished fifth and qualified for the Uefa Cup.

Fifth wasn’t good enough for a lot of people at the club. We had finished fourth and third in the previous two seasons so now the suggestion was that we were going the wrong way. Sir Bobby started getting a lot of the heat, which I found hard to take. He might not have won the title but when you consider where that club was when he took over and how quickly he turned an average team into being one of the top teams in Britain, it was remarkable.

I felt the manager was being undermined. Things started to happen I didn’t like at all. Like when Hugo Viana came up to me one day and told me he was going back to Portugal because he hadn’t been able to settle in England. We shook hands and then he put his finger to his lips. “You must keep it quiet,” he said, “because the manager doesn’t know yet.”

Other things happened that summer. Early in pre-season, Sir Bobby pulled me and Shola Ameobi to one side and said he wanted to talk to us about the rumours that were circulating that Patrick Kluivert would be joining the club from Barcelona. He said he realised that as strikers, we might both be unsettled by the speculation.

He said that Kluivert would not be joining the club. He said his sources in Barcelona told him Kluivert’s knee was not right and he was not living the right life. He said he had been a great player at one time and that he still admired him but he didn’t want to buy him. He told us not to worry. A week later, Kluivert signed.

I don’t think Kluivert was his signing. I felt he was signed by the board in a misguided attempt to appease the fans because we had not qualified for the Champions League. It worried me because I felt that it lessened Sir Bobby’s authority and that he found it hard to take. You could feel that he had less power. I started to wonder how much time he had left as manager of the club and I know I wasn’t the only one.

Sir Bobby was openly critical of the decision to sell Jonathan Woodgate to Real Madrid, too. He did an interview in one of the local papers about it which gave an interesting insight into the way his relationship with Freddy Shepherd worked.

“I only heard about this offer at 4.30pm on Wednesday,’’ Sir Bobby told them. “The chairman called me and asked to see me to discuss a private matter. I had no idea what. He then informed me that a bid had come in for Jonathan. I said to him: ‘You are aware that I don’t want to lose him, aren’t you?’

“Then I told him: ‘You are aware that we would be losing the finest centre half in this country?

“He replied: ‘I realise that.’

“I always wanted to fight and keep him but when Madrid came in, I knew it would be hard. But quite simply, if it had been my choice I would have kept him. Of course I would. We’ve just lost a great player and just how much of a blow that is depends on who we can get to replace him. Finding a replacement will be very difficult. Why should we pay £12m for a player who isn’t as good as Woodgate when we’ve sold him for £15m?”

There was a feeling of intrigue at the club. The chairman had spoken during the season about how finishing fourth should be the ‘bare minimum’ achievement and that there would be changes from top to bottom. The feeling at St James’ Park had changed. There was a restlessness there now that had not existed before.

All the talk after Kluivert’s signing was that he and Shearer were the new dream team in attack. That didn’t make me feel particularly great. Even Sir Bobby had told the press Kluivert’s arrival was as significant a moment for the club as when Alan had signed. I think he was saying what he had to say.

Shepherd talked about them being the dream team in a television interview, too. ‘We’ll see about that,’ I thought. It wasn’t that I had anything against Kluivert, by the way. How could you not be impressed by a player like him coming to your club? He was a lovely guy as well. He oozed class. He could caress the ball. He was another level from most of us in terms of his quality.

But his knee would blow up whatever he did. Even after training, it would swell. I felt for him because I knew what he must be going through. He was also in the midst of a divorce so he did a reasonable amount of partying. I knew if I got my knee right, I would be the main striker, and nailing down that place became my sole focus during pre-season.

We played a friendly against Rangers at St James’ Park at the end of July and I started up front alongside Alan. Darren Ambrose got injured early on and Sir Bobby asked me to play on the left but I said I’d rather stay up front. I didn’t want my versatility to be used as an excuse to accommodate Patrick although he wasn’t involved that day. Later in the game, I moved to the left as I was asked. It wasn’t a big deal. It was something that Sir Bobby and I discussed and reached an agreement about. He understood where I was coming from.

The biggest problem Sir Bobby had was that he lost Gary Speed that summer, too. Bolton Wanderers were willing to pay £750,000 for him and the chairman thought it was good business. He wanted to get Nicky Butt in from Manchester United and so Speedo went to Bolton. It was only when he had gone that most people realised what a huge gap he had left.

Speedo was the law in the changing room. When he spoke, he spoke. When he had a go, nobody spoke back to him. We were all in fear of him. He was the strict hard-liner. He would have a laugh and he would have fun but you made sure you worked when he was around and you knew how to work hard. Robson lost that influence when Speedo went and his dressing room changed. Sir Bobby lost his most important lieutenant among the players. If you want to know the moment when Sir Bobby really lost his job, it was the day when Speedo was sold.

With everything that was going on and the lingering sense of disappointment over the fifth-placed finish the previous season, we desperately needed to get off to a good start that season. We knew Sir Bobby was vulnerable but people had left and a lot of new players like Nicky Butt, James Milner and Kluivert had

arrived and we were all manoeuvring for position.

The first game of the season was against Middlesbrough at the Riverside but the trouble had started before we kicked off. Sir Bobby asked Kieron to play wide right because he wanted to start Jermaine Jenas and Butt in the centre of midfield.

Kieron said he didn’t want to. He knew he was at his best in the middle and he had seen me protest successfully about being played out of position at Rangers and thought he was entitled to do the same.

Things got out of hand this time, though. Sir Bobby refused to budge and dropped Kieron to the bench. Jenas and Butt started and Milner played on the right. I scored early on and Kieron came on for Milner 20 minutes from the end but Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink grabbed a last-minute equaliser for Middlesbrough that robbed us of the win we needed.

The issue with Kieron wouldn’t go away. Sir Bobby tried to cover for him but the news leaked out that Kieron had refused to play on the right and when he played for England in a match against Ukraine at St James’ Park the following Wednesday, he was booed every time he touched the ball. A couple of days later he apologised publicly to Sir Bobby.

It wasn’t a happy episode but the idea that Kieron was somehow to blame for Sir Bobby’s departure was totally false. And the notion that took hold that Kieron was the ringleader of a group who mocked Sir Bobby could not have been further from the truth, either. Kieron idolised him. If anything, as I’ve said, they were too close. They felt they could be totally honest with each other and when that honesty was expressed in public, others misinterpreted it.

Sir Bobby had a real soft spot for Kieron. Maybe it began as a shared history with Ipswich but they got on great. If Alan wasn’t playing or if he was substituted, Sir Bobby would always give the captain’s armband to Kieron. So, again, this idea that Sir Bobby had lost the dressing room and there was some kind of players’ rebellion led by Kieron was just a joke.

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella