- Home

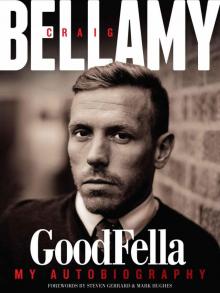

- Craig Bellamy

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella Page 17

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella Read online

Page 17

“And then someone like you calls me ‘a fucking prick’,” he said. “I’ll fucking knock you out.”

He was absolutely raging. He came over to where I was sitting and tried to grab me. I pushed his hand away and he lost his balance slightly and stumbled. That made a couple of the other boys laugh which made Souness even more furious than he was anyway.

“In the gym now,” he said. “Me and you.”

I couldn’t believe what was happening. He was going nuts.

“What are you on about?” I said. “I’m not going to go in the gym to fight you.”

He didn’t say anything else. He just stormed out.

I apologised later for what I’d said to him at Charlton. I meant it, too. I was out of order. He told the press he had taken me off because I had played two games for Wales the previous week and he wanted to save my legs. He said he wanted to persevere with me. He said I was ‘a cracking little player’. It was good to hear but we flew to Greece the afternoon after our row in the team meeting for a Uefa Cup match against Panionios and we never really spoke properly again.

I just wanted to get to January so that I could move away and begin my career afresh somewhere else. I knew Souness wanted me out and I wanted to go. It was a shame. I do have a lot of respect for him as a manager. He has given a lot to the game and I still think he has a lot to give even now.

Freddy Shepherd consistently said I was not for sale and I wasn’t going anywhere on loan.

But I got a different impression from the manager. January came around and one day I was sitting in the canteen at the training ground reading the newspapers before training. There was a big piece in one of them claiming Newcastle would listen to offers for me during what remained of the transfer window. It was confirmation I could leave, as far I was concerned. I knew who the journalist was and who he was friends with. It was a well-sourced story, put it that way.

Even though I wanted to go, I felt I was being badly treated. I was playing out of position and I was being cast as the villain. I was bewildered but I was angry, too. I said as much to some of the players in the canteen. I went out training but I was a shadow. My head was gone. I felt betrayed. I had my own issues as well at that time, as I’ve said. I felt worthless. I tried to train. Shay Given went to throw me a ball and I sort of turned my back on him.

I have never done that. I just said ‘sorry, mate’ and walked off. I told the coach my hamstring was killing me. I went in and Souness passed me on the way out. I saw the physio. I told him I wasn’t injured. I said I just needed to get off the training pitch because I had a chance of getting an injury because I wasn’t mentally right to train.

When training finished, Souness came to find me.

“Me and you,” he said, “we are going to see the chairman right now.”

So we went to his office at St James’ Park. He sat on one side of his desk. Souness and I sat on the other.

“Did you walk off the pitch with an injury?” Freddy asked me.

“Yes.”

“Are you injured?” he said.

“No.”

There was a pile of newspapers on Shepherd’s desk. I told him to get the Daily Mirror out and look at the article that claimed the club would listen to offers for me.

“I know it’s come from someone in this room,” I said.

“It’s nothing to do with me,” Souness said.

“I don’t even know this journalist,” Shepherd said, looking at the byline. “I’ll ring him now. But don’t believe what it says. You’ve got a lot of years left here.”

Souness butted in.

“Only on my terms,” he said.

We all agreed to agree on that. I shook their hands, apologised for walking off the training pitch and walked out.

That Sunday, we were playing Arsenal at Highbury. Souness named the team before we left and I wasn’t in it. He was making a point. I was fine with that. It was right that the other players should see that I had been dropped for walking off the training pitch. On Saturday, I travelled down to London with the rest of the squad.

When we got to Highbury on Sunday, Souness came over to me in the changing rooms.

“You’re not getting changed today,” he said.

He hadn’t even put me on the bench. There was always one player who was brought along and would be surplus to requirements unless somebody pulled out right at the last minute. This Sunday, he had decided it would be me. So he had made me travel all the way down to London for a high-profile match that was live on television and I wasn’t even on the bench.

People were surprised. A couple of the Sky reporters came up to me and asked if I was injured. I told them I wasn’t. Sky started reporting that I had refused to play. I was astonished. I began to feel like this was some sort of stitch-up. Why would I travel if I had refused to play? Highbury was a tight little ground. There was nowhere for me to get away from the spotlight and the questions. I felt exposed.

We lost the game 1-0 to a Dennis Bergkamp goal. It meant we had only won three of our last 10 matches. I got on the coach outside the ground and waited for the rest of the lads. The radio was on. They were reporting that Souness had implied I had refused to play. Actually, I think he was probably dropping hints about me walking off the training pitch but the message got lost in translation. Anyway, I was fuming. I wasn’t ready to accept that. I had a decent rapport with the Newcastle fans and I didn’t want them to think I had refused to play.

When we got back to Newcastle, I went out and drank like you wouldn’t believe. My head had gone. I ended up in a club somewhere with Patrick Kluivert. I woke up the next morning with a shocking hangover, rang Alan Shearer and had a go at him. That turned into quite a big argument and I said things I shouldn’t have said. Then I had the bright idea that I should do a television interview to put my side of the story.

It was one of the most ridiculous things I have ever done. I thought it was me against the world, which was rubbish, but I was in a mess by then. I did the interview with Sky and accused Souness of telling ‘a downright lie’ about me. I said it was part of a plan to hound me out of the club. There was a lot of confusion about exactly what I was being accused of and maybe if I had kept my counsel, it would all have blown over. But the interview put paid to that.

Freddy Shepherd was livid. He made a statement to the media then, in which he accused me of breaking a promise to apologise to the rest of the players for walking off the training pitch. “In my book,” Shepherd said, “this is cheating on the club, the supporters, the manager and the player’s own team-mates. Craig Bellamy is paid extremely well by Newcastle United and I consider his behaviour to be totally unacceptable and totally unprofessional. The player will now face internal discipline by the club.”

I was fined two weeks’ wages, £80,000, but I was not put on the transfer list. Shepherd phoned me and said I had to go and apologise to Souness. Only if I did that could I play for the club again, he said. I couldn’t do it. It was too far gone anyway. It was done. There was no way back.

So when I went into training the next day, I wasn’t allowed to go outside with the other players. I was told to stay in the gym and forbidden from mingling with the rest of the lads. People I thought I knew at the club, people I thought were my friends, wouldn’t be seen anywhere near me. They were worried that might be construed as taking my side. I did a few weights and then went home.

Birmingham City offered £6m for me and Newcastle accepted it but I didn’t feel ready for a permanent move. I wanted to see out the season on loan somewhere, repair my reputation a bit and then see what happened in the summer. I knew people would be looking at me as damaged goods after what had happened with Souness and I didn’t feel good about myself either. I was deep in self-loathing. I was low.

Then John Hartson rang me up. He had moved to Celtic after we had gone our separate ways at Coventry and he said Martin O’Neill wanted to take me to Scotland. I loved the idea. I fancied the chance of chasing the le

ague and trying to win a cup. I knew all about Celtic and their terrific support. I thought it would be a good experience.

Things began to get a bit frantic. Celtic approached Newcastle about loaning me but Newcastle turned them down. It came to the last day of the transfer window and things didn’t seem to have moved on. I went in to training at Newcastle. I wanted to show I was committed and willing to play. I didn’t want any more stories about me refusing to play.

I had only been there two minutes when I got a phone call saying the loan deal to Celtic had been agreed. I drove north straight away.

17

Cursed

Iwas looking forward to playing for Martin O’Neill. I didn’t really have any contact with him when he was the manager at Norwich because I was still an apprentice then but I knew there was an aura about him and something that made players want to play for him. I knew his assistants, John Robertson and Steve Walford, too. I met Steve as soon as I arrived in Glasgow. He hadn’t changed. He didn’t seem to give a shit whether I signed for Celtic or not. I signed anyway.

That was the way Steve operated. He had that rare talent of being able to make people like him despite being rude to everyone he met. Not caring was what he did. Some of the boys who played for Martin at Leicester told me that Walford was the same there. He used to stand on the touchline at training, telling the boys to hurry up and finish because he wanted to get down the pub. He was a very difficult guy to impress but if he’s not slagging you off, you know you’ve done all right.

While I was driving to Glasgow, John Hartson had called me. He warned me that the media up there was different to anything I would have experienced before. He said they were a law unto themselves and that they did whatever they wanted. I laughed at the idea it could be any worse than what I had been through at Newcastle.

There was a little silence at the other end of the line. “It’s worse,” Harts said.

He said they would be out to get me. He said that the poison had already been laid down for me and that some people from my time in England had already been on the phone to some of the press lads telling them to give me stick. And the first few weeks I was there, I was followed relentlessly. Everywhere I went, everything I did, there were photographers and reporters not far behind.

I was looking forward to making a fresh start but it was the first time I had moved clubs in the middle of the season and it was difficult. It didn’t sit easily with me that I had effectively abandoned Claire and the boys in Newcastle. It wasn’t easy for them. They were like the survivors of a shipwreck, clinging to what was left. And there wasn’t a lot left.

Claire felt shunned by some of the other wives. My departure hadn’t exactly been a model of good grace. And Ellis got a bit of stick at school from other kids. Children can be nasty sometimes so he was teased. He still had to finish his school year off. Terry McDermott did an interview in the one of the local papers that slagged me off. Claire and the kids got more grief. There was no point in them coming up to Scotland with me for a few months but they had a rough time.

I was okay. At least I had football to keep me occupied. I was lucky, too, in that I was surrounded by a great bunch of lads. Chris Sutton, Neil Lennon and Alan Thompson really welcomed me into the group and made sure they looked after me. I couldn’t have been with a better bunch of boys. Lennie put his arm round me and said ‘you’ll be okay here kid’. He took it upon himself to make sure I ate with him every night and that I wasn’t on my own. If Lennie was busy, he got his mate Marty to keep me company. I’ve never forgotten that kindness.

The spotlight was intense. About a week after I arrived, I made my debut in an Old Firm match. I’d heard all about the atmosphere in those Glasgow derbies and the build-up and the atmosphere in the ground. I thought I’d take it in my stride. I was used to big games, I had played in other derbies. But everything people had told me was true. The atmosphere got to me.

I felt like I couldn’t breathe. I was being watched everywhere. Glasgow was a tough city. You were adored and you were hated. Even I realised I had to tread carefully. In the papers, I was the favourite to score, the favourite to be the first to be sent off.

The night before the game, people from a neighbouring building rigged up some contraption that allowed them to fire water bombs across on to the balcony of the apartment I was renting. I wasn’t there. I was with the team at a hotel but my family was staying there. It was ingenious but it gave them a hell of a shock.

We had a small lead over Rangers in the SPL when I arrived and when I looked at the Celtic side, I wasn’t surprised.

We had Sutton and Hartson up front, Aiden McGeady and Alan Thompson on the wings, Lennon in midfield. But after everything that had gone on at Newcastle, I didn’t really feel ready to play in that first match against Rangers at Celtic Park. I was still a bit frazzled. We lost 2-0.

Then there was a period of almost three weeks when we didn’t play because bad weather wiped the fixtures out. We went up to Inverness to play against Inverness Caledonian Thistle and the game was called off the next morning. The night we were in Inverness, someone staggered into a police station in Glasgow and said they had just been assaulted by Craig Bellamy.

Inverness is about 200 miles from Glasgow. Funnily enough, they didn’t press charges.

When the weather improved towards the end of February and football resumed, I was ready. I played well. I made a decent contribution. The first game back, we played Clyde away and won 5-0. I got the fifth. I scored again against Hibs a week later and I got a hat-trick against Dundee United at Tannadice in a 3-2 victory. I was desperate to win the league up there. I thought it would be some form of validation for my career so far. Everything seemed set fair.

I loved playing for O’Neill. It’s very basic. There is no miracle to what he does. There was no secret, for instance, to why we were so dangerous at set-pieces. Just get someone with Alan Thompson’s quality who can deliver the ball where he wants to and go and attack it. He would go and buy big defenders who could attack the ball. It was that simple. He had uncomplicated instructions. Make sure you are first to the ball in our box and in theirs. Let the good players play.

Usually, he turned up on the Thursday or Friday before a weekend game, much as Brian Clough used to do when he was at Nottingham Forest. He had great charisma. He was so polite and well-educated, too, way too well-educated for us in football. It was best not to forget he was in charge, though. Sure, he was nice but if you weren’t doing your job properly, he would be scathing. If you ever answered back, he would never forget it. He gave some of the biggest rollickings I had ever seen.

But when you played well for him, you felt brilliant because he told you how good you were. And he told you in front of everyone so that everyone else could hear. He made you feel like you were the best player in the world. And the spirit he fostered at the club was the best I’ve ever seen. Not just among the players but among the entire staff.

If you got fined for being late, you didn’t put it in a kitty. You had to go and give the laundry woman £500 or give it to the cook. That made you feel great then, even though the gaffer had told you to do it. It turned you from feeling you were being punished to feeling that you were doing something good and worthwhile and generous.

Because my family was still in Newcastle and I didn’t want to spend my days in an empty flat, I would stick around at the training ground in the afternoons. I would do my weights and then play pool with Robbo and Stevie Walford even though they spent all day and every day chain-smoking, which wasn’t great for my asthma.

When they weren’t playing pool, they watched the History Channel. They were obsessed with crimes. More accurately, they were obsessed with criminals. They loved mass murderers. They were totally fascinated by them.

Now and again, they’d get into big arguments about how many people one of the murderers had killed or what method he had used.

They shared that hobby with Martin. Martin used to go to court to watch ca

ses unfold sometimes. He was fascinated by the JFK assassination and the story of the A6 murderer James Hanratty. I enjoyed being in his company. He was such a good bloke. The other two could be rude and unpleasant but they were fun. Martin was different. He never looked you in the eye but his manners were outstanding.

We beat Livingston 4-0 away in the middle of April and even though I didn’t score, I had a good game. Harts got a hat-trick and I set a couple of them up for him. I was given the man of the match award but the next week, one of my ex-teammates at Newcastle rang me and said Shearer had been laughing about me.

“What about your mate,” he’d said. “Celtic batter someone 4-0 and he can’t even get on the scoresheet.”

That was Alan all over. If you didn’t score, it didn’t matter how well you played or how much work you did for the team.

The following weekend, we beat Aberdeen 3-2 and I got the winner late on. After the game, we flew to Ireland for a bit of a break. We had a good night out in Donegal that night and the following day, Chris Sutton, Neil Lennon and I went out to a bar to watch the FA Cup semi-final between Newcastle and Manchester United. Manchester United won comfortably. I felt bad for Newcastle. They lost 4-1 and they were never really in it.

Afterwards, Alan did a television interview. He mentioned shortcomings in defence, which made me laugh. Alan needed to look at himself a bit more. He wasn’t the player he had been and now he was trying to pass the buck.

When a player’s time comes, it comes. Alan had become determined to break Newcastle’s all-time club scoring record, which had been held for nearly 50 years by Jackie Milburn but his goals were drying up and I didn’t think he was offering the team enough in general play to justify his place. He was becoming an obstacle to the club’s progress. It was sad because I had so much admiration for him as a player and I learned so much from him. But time had caught up with him.

As I watched him giving his interview, some of the bitterness I felt towards him over Bobby Robson’s departure welled up inside me. I had seen the semi-final. I had seen how poorly he performed personally. I thought it was wrong for him to do an interview afterwards in those circumstances. If I don’t perform anywhere near my level, I’m certainly not going to talk about what we didn’t do as a team. So I got my phone out and texted him.

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella