- Home

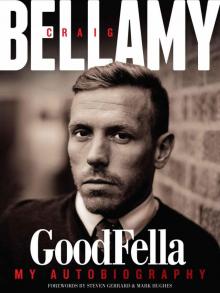

- Craig Bellamy

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella Page 3

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella Read online

Page 3

So I was playing for Norwich, then going back to Cardiff and hanging round with kids who were drinking and smoking. It seemed the coolest thing to do at the time and I felt pressure to be a part of it. I started having a few drinks when I was 12. The odd bottle of cider, a beer here and there. I stayed away from cigarettes because my old man told me it would make me slow and I would lose my pace. I didn’t want that.

After being introduced to alcohol, I drank fairly regularly. Maybe it was another way of chasing girls. It gave me a bit of Dutch courage. I felt I had to do it, which was a weakness in me. All my friends were doing it and although I knew it wasn’t right, I didn’t want to be on my own.

So I would go off and drink with my mates. My parents caught me a few times and I can’t imagine what was going through their heads. Then, I saw other kids smoking cannabis and on other drugs. Glue was frequent around the area. At first, I viewed those people as down and outs. But I started seeing people who were close to me smoking cannabis and doing air fresheners and it started to seem normal.

Glade, the air-freshener that was sold in those tall, thin canisters, was a big thing round our way. You put a sleeve over the nozzle at the top and pumped it and sucked through it. Apparently, you got a ridiculous head rush for five or ten seconds and then you did it again.

Being left on my own was too hard to contemplate at that age. Some of them were trying to lead me down a particular behavioural route because maybe they didn’t want me to have success. They knew about my other life in football and the chance I had. Others could see that I was risking everything just by hanging around with them. Some of them would say ‘Bellers, no chance, don’t do it’. They wanted to protect me.

Perhaps inevitably, some of my mates started getting into trouble. If they were buying £15 worth of cannabis, well, they had to get £15. A lot of the people who sold it let them buy it on tick. They would give you a deadline and you had to have the £15 in four days or a week.

If you’re a kid, you don’t have the discipline to save up. So you have to find another way to get the money. They turned to crime. The main target was car stereos, the pull-out ones. It was like a dream if you found a car with one of them. People were looking for pull-outs like you wouldn’t believe. It was an easy way out. It would be a window, an elbow through it and ‘bang!’ You could sell that pull-out for £25. If it was a Panasonic, brilliant. If it was anything else, a different make, you could still get a few quid.

I used to hang out with mates who did that. Generally, it was more about me going along and watching them do it. I would keep an eye out for them while they were stealing from the cars. I never physically stole anything myself but I know that’s no excuse. Helping out is just as bad as stealing.

There was a period when I was 13 or so when I was skiving off school quite a lot. Once, I went missing for two weeks. How can you go missing for two weeks as a 13-year-old kid without anybody from school ringing up? But they didn’t.

The only reason I got found out was because another lad got caught. His mum was dragging him up to school and she made him grass me up to the head teacher.

Because a lot of my friends were a couple of years older, a lot of them just stopped going to school. One or two of the boys in my class got expelled. A mate called Bingham was expelled for abusive behaviour. He wasn’t that kind of kid but when he got up to read in class and the other kids started sniggering, he would feel so embarrassed that he would shout at the teacher. He went to another school and got expelled again. And his parents wouldn’t allow him to go to a special school, so he was 13 and not going to school at all.

Bingham was one of my best friends. His dad left for work about 7am and his mum left at ten past nine. I’d wait for her to leave and then I’d go in and wake him up and spend the morning at his house until his mum came back at lunchtime. And then I only had a few hours to kill before I could go back to my house, pretending everything was normal.

There’d be a few of us round Bingham’s house every morning. I kind of liked that excitement of being somewhere you shouldn’t be. It would be wrong to say I wasn’t concerned about my parents finding out but I also knew it wouldn’t be the biggest thing in the world. I think my parents wanted me to learn but in the back of their minds they thought I was going to make it as a footballer with Norwich so they weren’t quite as bothered.

They were right about Norwich, too. I began playing for the club’s schoolboy team and when I was about to sign schoolboy forms, a couple of other clubs tried to tempt me and my family away. Leeds United offered my parents £10,000 for me to go to sign with them and Norwich fought them off by guaranteeing me a two-year YTS apprenticeship when I was old enough to take it up.

We took that like a shot but it was one of the worst things Norwich could have done for me. My life after school was sorted now, so what did I need to go to school for? That was my attitude. My friends weren’t going, so why should I go? My parents would have come down hard on me for not being in school but as long as they weren’t confronted with it, they turned a blind eye. They didn’t chase it up and the school didn’t ask them about it either.

When I started playing for the Norwich schoolboy teams, I would get the 4.25pm train from Cardiff Central to London Paddington on Saturday afternoon. I’d get the Tube from Paddington to Liverpool Street and another train from Liverpool Street to Norwich, which got me in at 9.10pm. I’d play for Norwich’s schoolboy team on Sunday morning, then get a train back to Cardiff. My dad would come and pick me up.

Usually, I brought a bonus home with me. We used to get expenses and the older lads played the system. They’d claim £100 for their fare, whatever it actually was, and they would have killed me if I’d only put in for the £25 it cost me for the Cardiff-Norwich return. So I claimed the same as them and when I arrived home in Cardiff, I’d give my mum and dad the £25 and keep the rest for myself.

On a Monday, I’d often be walking into school with £75 in my pocket. That’s if I went into school, which I usually didn’t. I had begun to feel I could do whatever I wanted and pay for whoever wanted to come with me, too. So I’d spend the money on booze or have an entire day at an amusement arcade somewhere. Or if I liked a pair of trainers, I could get a pair of trainers. Or I could buy some cigarettes. I could do whatever I wanted and I usually did.

I learned absolutely nothing at school. That was my fault most of all but there was a lack of enthusiasm from the teachers, too. They seemed weary. They seemed to have given up. Before every class, the teacher would say ‘if you don’t want to learn, go and sit at the back of the class and don’t interrupt the kids who do want to learn’. I was a kid who knew he was going to be a footballer and thought he knew it all. I would go and sit at the back, daydream and kill a couple of hours. I deeply regret that. I wish I had knuckled down and picked up as much as I could but I lived another life.

I was soon drinking and smoking cigarettes every day, ignoring my dad’s warning. My football started to go downhill and because of the lifestyle I was leading, I wasn’t maturing like other kids, who were getting bigger and stronger. By the time I was 14, I was drinking more and more. I’d started off on cider and moved on to cheap lager. There was no way I looked 18 but it was all easy enough to get hold of round our way. If there was a lad walking past the off-licence, we’d ask him to buy the drink for us. Usually, they’d do it if you gave them a box of matches or a packet of Rizlas. It couldn’t have been simpler really.

Drinking was taking a bigger and bigger toll on my football. During the Christmas holidays at the end of 1993, there was a residential week in Norwich that was used to decide which of the kids in the schoolboy team would be signed up to apprenticeships. My place was already guaranteed but it was made clear to me that week that the Norwich coaches felt I was going backwards.

I was playing for Wales Schoolboys, too, and things weren’t going well there, either. We barely won a game. We were a poor, poor team. There was a lot of infighting and jealousy. Some of th

e parents of other kids had been ringing up the manager, apparently, and saying that I was too small to be in the team and wasn’t worth my place. The manager even singled me out after one defeat and asked me in front of everybody whether I thought I deserved to be playing.

I told him that, yes, I did think I deserved to be playing but inside I was starting to have doubts about whether I wanted to be a footballer. We were losing and I did begin to feel that maybe I wasn’t good enough. In a way, those kinds of thoughts are what made me a top player. I have always been haunted by self-doubt. I have always wondered whether the next game or the next move is the one that will find me out and expose me as the ordinary player that deep down I fear I am.

The way I was living my life was eating at me, really gnawing away at me. I hated myself for my lack of discipline and the weakness I was showing with my drinking and smoking. I knew it was affecting my football but I felt torn. I was 14. It’s young to have to dedicate yourself to something. It’s young to cut yourself off from your friends.

I wanted to fit in. I wanted to be one of the lads. I was going through puberty, too, of course, and I started to entertain the idea that maybe I would like to do what my mates were doing. There was a freedom about that.

I knew how hard I was going to have to work if I was to become a professional footballer and I didn’t know whether I wanted to work that hard. No one from the area had ever done it. I had no one to look up to. There was no role model for that, no example to follow. I started to think ‘what’s wrong with what my mates do, would it be so bad to stick around in Cardiff and drift along with them?’

I don’t know if I could say there was a low point, a point of maximum danger, a moment where I realised I was risking more than my football career. Perhaps it was the time I rode in a stolen car. I only did it once. I was skiving off school with a mate and a lad pulled up who was known around the area for stealing cars.

Me and my mate jumped in and this lad screamed up the road to my school and roared out on to the playing fields. All the other kids were in the classrooms staring out of the windows at us and this lad pulled a couple of doughnuts on the football pitches and then drove back out on to the streets. When we got a couple of hundred yards away, I asked him to let me out. I was scared stiff. I hated every second of it. I thought then ‘I am never, ever going in a stolen car again’.

That episode still haunts me now. It was one of the stupidest things I have ever done. What if it had crashed? I could have lost everything. The other thing that haunts me is the mate that was with me carried on riding in stolen cars with the lad who was driving. He ended up stealing cars with him. He started taking heroin. He travelled along a different path.

Perhaps most people are like this but when I did the wrong thing, I always had a voice in the back of my head telling me to stop. I always had a limit.

When glue came into my little group of mates for a couple of weeks, I remember putting the bag to my mouth once and wondering what to do. In that split-second, I thought about this young kid who was well-known in our area for being a gluey. I had an image of him in my mind, thin and miserable, with cold sores all around his mouth and his face red and raw. I didn’t want to look like that. I thought ‘no’. I put the bag down and passed it on.

I was always aware of what went on and I knew what older kids were doing because you would see them smoking stuff and it wasn’t just cannabis. I realised quickly that the ones who were doing hard stuff didn’t look great. It was the people who were selling it who were clever. They would be around boys my age with wads of cash, exploiting the image that they were flash and super-successful. A lot of impressionable kids loved that.

You know what I thought? I looked at them and I thought ‘great, but this is bullshit’. I saw the drug dealers hanging around and I saw the local kids heading up to the Trowbridge Inn, the pub that was the focal point of our community.

Some of my mates had to go up there if they wanted to see their fathers because they were in there all the time. They couldn’t wait to grow up so they could go and start drinking in there, too. My dad wasn’t like that but I knew I was close to choosing that way of life. The drink, the glue, the Glade, all of it. I knew that was how life could go for me. I could see how it might work out.

I knew some of the older boys were starting to make appearances in court. I could see the route their lives were taking, where it was leading. All the time, I looked at what was going on around me, at the kids trooping up to the Trowbridge Inn, at the little circles of kids sniffing glue and a thought kept going through my mind.

“There has got to be more to life than this,” I kept saying to myself. “There has got to be more.”

3

Life Changer

In those months, I came incredibly close to blowing it and never having a football career. One of the things that saved me was meeting Claire. Claire and I got divorced at the end of 2012 but we had been together from the day at the end of 1993 when my brother, Paul, came up to me and told me that she fancied me. I met her on the corner and we had our first kiss. We quickly became inseparable and I began to spend less time with my mates. Suddenly, it was Claire who was my focus, not sitting round with my pals, drinking.

The following summer, it was the 1994 World Cup and even though people don’t remember it as one of the great tournaments, it helped me fall in love with the game again. I made up my mind I was going to watch every match. I loved studying Roberto Baggio and Romario. I had a brilliant summer and I felt like football had become my priority again. I came back from the brink at a time when some of my mates were falling over the edge.

I was lucky in other ways, too. I had a great relationship with my nana Mary, my dad’s mum. She looked after me and my brothers from an early age because both my mum and dad were often at work. So I would spend most of the school holidays in Adamsdown, quite close to where we used to live in Splott, with my nana, my brothers and my cousin Sarah.

I thought Nana Mary was unbelievable. She showed us pure love. We had to kiss her when we came in and kiss her before we left. She was a lovely woman who wasn’t scared of showing emotion. She was also an important influence on me. My parents would never have a real go at me if I did something wrong but my nana would and I felt more guilty letting her down than anyone. I adored her. She was a brilliant, brilliant woman.

It was in that summer of 1994 that I began to realise that my time in Cardiff was almost at an end. I was dreading leaving. There might have been social problems in Trowbridge but I still loved it. It was what I knew. In my area around Trowbridge Green, every door in every house was open. There was music playing in the street. You could walk into anyone’s house.

And inevitably, some of my happiest memories are simple ones linked to football. I remember the 1990 FA Cup semi-final when Liverpool played Crystal Palace; flitting from one mate’s house to another. I went into one house and Ian Rush had scored, then popped into another house and someone else had scored and suddenly Alan Pardew was scoring the goal that won it in extra-time for Palace and it was 4-3. And then after the match, the ice cream van appeared in the street and it was carnage.

But those days were gone. Things had moved on. Some of my mates had already gone to jail for crimes they committed trying to feed their drug habits and it had got to the point where my dad actually wanted me to go to Norwich because he was so worried about what might happen to me if I stuck around at home in Cardiff.

Norwich wanted to move me over to the club early but they were restricted because of my school age. But I wasn’t going to school anyway, so one way and another, I started spending more time in Norwich. I began playing for the youth team and the more football I was getting, the more they were coaching me and improving me.

I still found the final separation from home very hard when it came. I joined up on July 1 and the night before I left, it dawned on me that this was it. I knew life was changing. I knew life was never going to be like this again. I knew I had to do it or

I was never going to be a footballer.

Leaving Claire was very difficult. She was still at school. There was no possibility of her coming to join me and I worried we would drift apart. And suddenly, simple parts of my routine that I had taken for granted, like hopping on the bus to go and see my nana, seemed unbelievably precious now that I knew I was never going to be able to do them again. These are the rites of passage that many kids go through when they leave home but I was 15 and I found it very tough.

It had an impact on those around me, too. My elder brother and I were two different people but I was close to my younger brother. He was my kid brother and we shared a bedroom when we were kids and I was very protective of him. When I look back on it now, I feel for him because I moved away at 15. One minute your big brother is looking out for you and the next he is gone.

He was at a difficult age and all of a sudden, he was alone. We have drifted apart since then and I think it’s because I moved away at a young age. It wasn’t just the geographical separation. It puts a psychological barrier between you, too. Me moving away as young as I did affected a lot of relationships in my close family. That determination to make it, it can set you apart.

My mum and dad drove me up to Norwich. My dad had been counting the days to me leaving because he knew the dangers I was facing at home. My mum was different. She would have been happy if I’d said I wanted to come back home. She would have driven me right back to Cardiff there and then. She was losing her 15-year-old son and it was tough for her. My father told me later how upset she was in the car on the way back but she couldn’t show that in front of me. She thought she had lost me, which she had. I wasn’t going to be there any more.

In many ways, I think the pain of that separation and what I endured in the following weeks and months shaped the person I became. That first year of my apprenticeship at Norwich was the hardest year of my life. For the first few months, I cried myself to sleep most nights. I learned to cope on my own. I didn’t ever turn to others.

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella